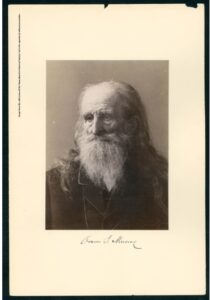

Historian Dan Billin

Last night, the Quechee Club hosted the lecture “Mobocracy vs. Abolitionism,” by New Hampshire historian and former newspaper reporter Dan Billin. Sponsored by The Quechee Club’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I) Council, the event examined anti-abolitionist mob violence in New England in the 1830s, as well as the bravery of Black students at the progressive, racially integrated school, Noyes Academy, in their fight against slavery.

While Billin’s typical lecture focuses solely on Noyes Academy when he speaks at events in New Hampshire, his talk at the Quechee Club incorporated broader regional conflicts between abolitionists in Vermont and the Granite State, as mob violence became a tactic used by those opposed to the freeing of slaves.

“The abolitionist movement really heated up in the early 1830s, and it was a very activist movement, very radical. And 1835 pretty much set the country on fire,” said Billin. In that year, pro-slavery mobs rioted in cities including Boston, where leading abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was dragged through the streets — in order to be tarred and feathered — before he escaped.

“The immediate abolitionists wanted an immediate end to slavery, and it scared people,” said Billin. “There had been a recent slave uprising in the South — Nat Turner’s uprising, in which white people were killed. People in the South lived in fear of their slaves, who outnumbered them tremendously, and feared that the violence they [themselves] employed might fail to keep [the slaves] in check and keep them obedient. And so they saw the abolitionists as a mortal danger to people in the South.”

In 1835, abolitionists acquired a business mailing list in the South and began to barrage them with abolitionist pamphlets and flyers, which caused further panic in pro-slavery Southerners — who then labeled the Northern abolitionists as “anti-American,” according to Billin. And while racism in the antebellum South is common knowledge, Billin’s special focus of this lecture was on the Northerners — particularly in Vermont and New Hampshire — who also viewed abolition as a threat to their white livelihoods and their notions of what America should be.

Baptist minister and abolitionist Orson Murray was threatened by a pro-slavery mob when he tried to speak in Woodstock in 1835.

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

“I’m telling a fuller history of the attitudes of Vermont and New Hampshire towards slavery in the decades before the Civil War,” said Billin. “Vermont prides itself on having been the first state to outlaw slavery in its Constitution in 1777, but the truth is that slavery didn’t just divide the North from the South, but also Northerners from each other. Both Vermont and New Hampshire were hotbeds of racist hatred and violence.”

One of the tactics used by anti-abolitionists in the North was to intimidate and even cause violence to abolitionists speaking at churches, town halls, and courthouses, said Billin. “In Newbury, Vt., they got out the fire pump, and they opened the church door, and they turned the hose on the abolitionist speaker. In Brattleboro, they got out the militia cannon, and they fired it continuously during the appearance of an abolitionist to make it impossible for him to complete his presentation,” he said.

Here in the Upper Valley, in Canaan, N.H., anti-abolitionists formed a town-hall-approved mob and literally dragged the schoolhouse of Noyes Academy — one of the nations’ first integrated schools, and one that attracted Black students from around the Northeast — a half mile with oxen in order to declare it a school for white children only, while simultaneously terrifying the Black students with gunfire, cannon fire, and death threats until they left the town.

Racist mobs existed right here in Woodstock, too.

“There was violence against abolitionist speakers in Woodstock, Vt., and I’ve come across items from papers in Woodstock. A couple of them were very anti-abolitionist,” said Billin. He shared with the Standard an 1835 clipping from Garrison’s prominent abolitionist newspaper “The Liberator,” a reprinting of an article in Vermont’s Middlebury Free Press, which detailed Baptist minister and abolitionist Orson Murray’s recounting of his mob-thwarted attempt to speak in Woodstock. In a dramatic turn of events, the leader of the mob that had prevented Murray from speaking in Woodstock was physically beaten by Murray’s supporters in South Woodstock.

Billin, who is on the speaker’s bureau of the New Hampshire Humanities council — which partners with and has historically received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) — mentioned Trump’s executive orders to slash Congressional funding for the NEH, particularly grants geared toward anything related to DEI, as part of an attempt to excise slavery and racism from national awareness. Billin added Trump’s executive orders to remove from federal property plaques and imagery around the realities of slavery — including a slavery exhibit at the historic President’s House site in Philadelphia, just last week — as other examples of this attempted historical erasure.

“I’m telling forgotten history about slavery and race relations at a time when the federal government is actively trying to suppress and obscure the fuller truth about the same thing,” said Billin. “There is a struggle at this moment in the country over whether people can and should tell the kind of stories that I’m telling.”

Myrna Brooks, chair of the education and awareness committee of the Quechee Club DE&I Council — founded in 2020, and part of the Quechee Lakes Landowners Association — told the Standard that this is the second or third lecture the council has brought to the community.

“One of the common comments we hear is, ‘I’m so glad you’re doing this. You seem to be the only one in our area that’s offering education and awareness about racism and diversity and equity,” said Brooks. “Our goal is to explore inequities experienced by Black and indigenous people of Vermont and the Upper Valley.”